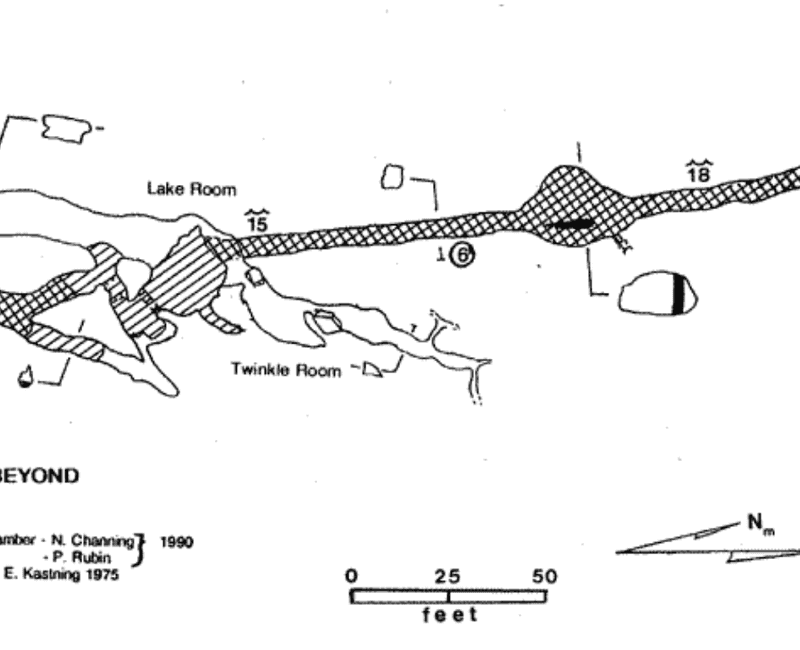

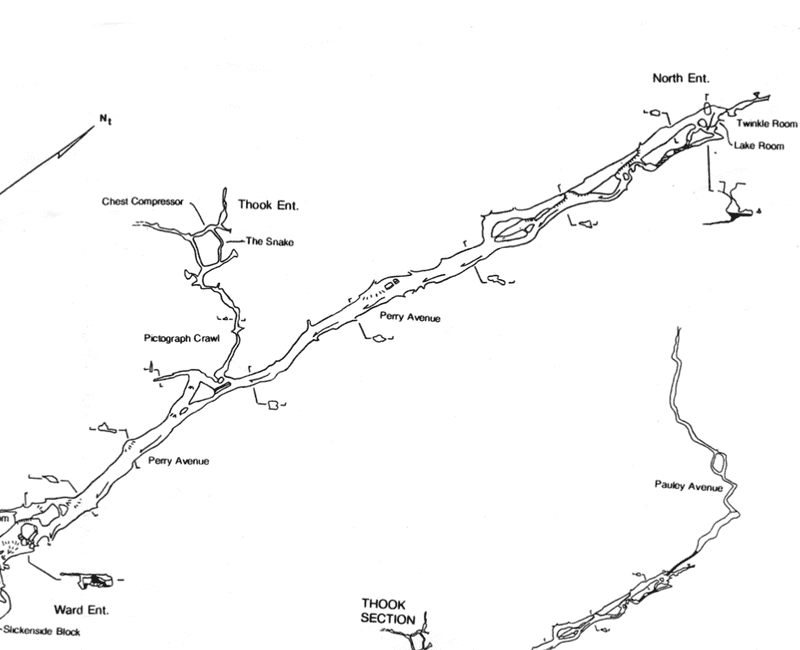

Three and a half hours from Boston, in Albany County NY resides the most visited and likely best known wild cave of the Northeast - Clarksville. Having visited Clarksville Cave the previous summer with the Boston Grotto, and being immensely intrigued by the sump residing in the cave’s terminal room, the Lake Room, I wanted to try diving the sump. I hoped if the sump were passable and conditions favorable, I’d eventually end up in the nearly never visited Pauley Avenue tunnel - a likely 1000ft section of pristine dry passage.

After being generously granted permission to dive from the Clarksville preserve managers, a few friends, Boston Grotto members and myself drove up to Clarksville for a checkout dive on June 5th.

Clarksville Cave is a generously sized horizontal cave (for the Northeast) and permits upright walking for the majority of the 1000ft walk to the Lake Room. Some lower sections require duck-walking through waist deep water, but these sections are fairly short and relatively painless.

The First Attempt

I packed my standard sidemount kit consisting of an Xdeep Stealth harness, Diverite XT regulators, and LP50’s for size and portability (sorry beloved LP108’s - not today). I considered AL40’s, but I didn’t have any with left/right valves and I’d have to carry extra lead to offset their buoyancy. With LP50’s I can just barely get away with being weightless.

With my gear divided up four ways (between myself, Elisabeth, James, and Alex), the haul to the sump was fairly easy. Once at the water, James helped me kit up and I delicately knelt into the (surprisingly) crystal clear pool. At a bracing 42 degrees, what small amount of exposed skin I had was frozen up pretty quickly. I was thankful for the decision to go with dry gloves. Looking around, it was pretty obvious that there was only a singular depression of any sort that looked like it could possibly have been the entrance (I’d later learn this depression was alas, not the entrance I was looking for). I’d been warned that it was likely the entrance had been filled in substantially and would likely require some significant excavation effort.

Approaching the depression, it quickly became apparent that there was a substantial amount of debris that would need to be removed. To make matters worse, the depression was situated under a large ceiling slab that had perched itself on the wall of the basin and the floor, forming a triangular entrance of sorts. This massively complicated debris removal by requiring a backwards shimmy out of this triangular entrance any time I wanted to discard rock or other refuse. Additionally, (and unsurprisingly) touching nearly anything in this entrance resulted almost instantaneously in degraded visibility. After removing a few decently sized slabs from the hole, I’d quickly ended up working in zero-visibility. Continuing this for a bit longer appeared to enlarge the entrance hole substantially, but without being able to see the hole, it was impossible to make a good judgment. After almost two hours in five feet of the bracing water, I called it quits.

The crystal clear pool we’d arrived at hours earlier was now reminiscent of chocolate milk. We dropped the dive gear in the truck, and set out for a proper introduction to caving in the Northeast. As this was Alex’s first caving trip (ever!) we reentered the cave and dragged him through the famed pictograph crawl (a very tight tunnel featuring floor to ceiling height of as little as 10 inches). Unfazed, Alex was now a true caver. At this point we were collectively frozen, so exited Clarksville once again and made our way to the NSS's Schoharie cabin to rest for the night.

The Second Attempt

Two weeks later, we returned with mutual friend Sam in tow for what would be her second ever Northeastern cave after leaving Pennsylvania and the Nittany Grotto. After meeting her during an icy trip to Slingerlands Hellhole a few months earlier, I’d managed to convince her to tag along. Alex also returned for a second round, thankfully proving that what was his first ever cave trip wasn’t actually that bad! With the same gear kit, we loaded up and drove out from Boston.

Navigating to the Lake Room was uneventful and we arrived even faster than our previous trip. James once again helped me kit up, assembled, rigged my bottles and brought them to the water (the benefit of having another cave diver in the group!) I tried to enter the water as delicately as possible and float face down on the surface - gaining the ability to inspect my work from last time.

Gazing into the hole, I could see I’d definitely made some progress - it was certainly larger than last time!

I quickly got to work, and resumed the debris removal process - visibility disappearing almost immediately once again. Though the majority of what I removed was rock, I also ended up removing a few sections of porous, heavily rusted pipe (I later learned this pipe was likely formerly used to remove water from the Lake Room for irrigation on a nearby farm). After a decent bit of work, the entrance was large enough for me to shim the majority of my shoulder in and feel around. With my arm fully in the tunnel I’d been working to clear, I could feel a distance of approximately eight inches between a solid rock ceiling and floor (or a massive, likely unmovable ceiling slab).

Alas, the dream of a going tunnel in the Lake Room seemed pretty hopeless. Even if I were able to clear what would be a massive amount of debris, it seemed pretty unlikely to me that the tunnel would actually be passable.

Followup

In further discussion with the preserve managers, it became pretty apparent that the entrance I was working to clear was at best a secondary entrance to the sump. It seemed likely that the actual entrance to the sump lay buried right where I’d been entering the water, and subsequently almost directly under where I’d been discarding the spoils! I also learned at this time that the Lake Room pool used to be significantly deeper, and was told “people often would jump in and not hit bottom in any of that part of the lake”. When we were in the cave, the pool was as roughly three feet at its deepest (short of the entrance hole I was working to enlarge). In my digging, the deepest point I was able to reach (within the entrance tunnel itself) was a mere seven feet. It’s clear the lake has filled in substantially.

Some weeks later, while staying at the Schoharie cabin for a weekend of regular caving, our group met a number of folks from the Central Connecticut Grotto. Among them were two folks (unfortunately who’s names I don’t recall - sorry!) familiar with sump diving in the area, and particularly familiar with Clarksville’s hydrology. After much discussion, the consensus was that the hole I was working in may or may not be an entrance (viability unknown) and that the true entrance was buried deeply under my gear staging area. It seems likely that due to the freeze-thaw cycle the northeast encounters yearly, numerous ceiling slabs have over time fallen and effectively sealed the true entrance.

Conclusion

Though the Lake Room sump in Clarksville poses an interesting objective, it seems that short of a gargantuan effort to restore the initial entrance to the sump - Pauley Avenue is sealed off forever. Though progress was limited, it was a fun project to try in the Northeasts most visited wild cave. A huge thanks to everyone that helped drag my gear to and from the sump in chilly conditions (Sam, Elisabeth, James and Alex)!